Hundreds of beds empty in special care homes while hospital patients kept in ambulance bay

Special care home operators are questioning Premier Susan Holt’s assertion that there’s no alternative to housing hospital patients in an ambulance bay without running water or bathrooms.

While acknowledging earlier this month that the makeshift unit at the Dr. Everett Chalmers Regional Hospital, known as the medical transition unit, is not acceptable care, Holt said it’s necessary.

“It’s pretty hard to say that it’s better than nothing because it is terrible,” she said. “But the alternative right now is, is is nothing is no care, no, no place to lay your head down.”

But several current and former operators of special care home disagree and are calling on the province to make better use of the care-home option.

Special care homes offer around-the-clock care to New Brunswickers. The province has 301 of these homes that are privately owned but regulated by the Department of Social Development.

Colleen and Marty Hood ran a special care home from 2012 until 2019.

The pair also recently had a loved one admitted to the Chalmers medical transition unit, fashioned out of an ambulance bay.

It’s been in use for at least a year, but the conditions were put into the public eye after a registered nurse working in Fredericton wrote a letter to the premier about her grandmother’s stay.

The Hoods both used the word “disgusting” to describe the unit.

Marty Hood, a nurse of 21 years, now teaches courses for the licensed practical nurse program at New Brunswick Community College.

“From a nursing aspect, if I’m nursing, and I went to wash you up and I get either vomit on my arm, or or I get some feces on my arm, where do I wash up? Where do I go?” he said.

“There’s no running water out there, so I have to walk somewhere else with this on me, which could be contaminating people, and wash my hands … this goes against everything that we teach students.”

Colleen Hood said the unit struck her as something that might be in use “in a third-world country” or while at war.

Over 500 beds vacant

Horizon and Vitalité health networks have both said many of their beds are taken up by patients who no longer need hospital care but are waiting for placements in some other level of care, such as nursing homes.

This has a ripple effect, including on patients who are admitted through the ER but must wait in storage or ambulance space for beds.

Marty Hood said the situation should prompt the province to review all of its “tools” and consider special care homes as a place for patients to stay, even temporarily, when they no longer need acute care.

“That would be better than the [medical transition unit] at the Chalmers hospital, or being in a closet at Saint John Regional Hospital,” he said.

“It’s absolutely disgusting what we’re doing to our seniors.”

According to the New Brunswick Special Care Home Association, more than 500 special care home beds are empty provincewide.

President Jan Seely said all of those placements to special care homes come with access to to nursing care through the extramural program.

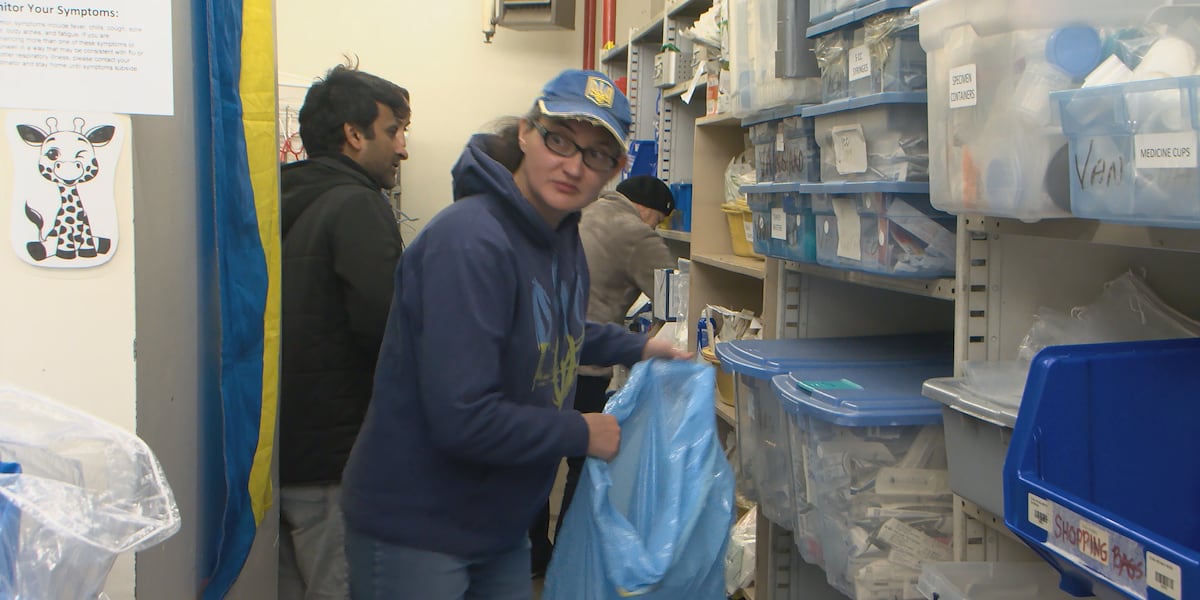

Mazerolle Special Care Home in Dieppe is one of the homes with empty beds, president Darlene Mazerolle said.

She would like to see the province fast-track patients out of the hospital and into available special care beds, as it did during the COVID-19 pandemic.

“Within a couple of weeks, they moved so many people out of the hospital. … The majority of them did great,” Mazerolle said in an interview. “So I don’t understand why everybody thinks there’s no solution. There absolutely is a solution, and they’ve done it before.”

Seely agrees that special care homes aren’t being used to their full capacity.

Most of the vacant beds offer Level 2 care, which give residents support with daily living, including meals, medication administration, and transportation to appointments.

But as of last week there were also 37 empty beds in special care homes that specialize in dementia and memory care, known as Level 3B.

There were also 18 vacancies in Level 3G homes, which provide greater on-site support for medical conditions — for example, residents who need help managing diabetes, or who use supplemental oxygen.

‘Broken system’

But there are also vacancies in nursing homes.

Nursing homes are different from special care homes in that they provide 24-hour access to nursing staff on site.

“As of October 2025, there were 182 vacant nursing home beds across New Brunswick,” the department said by statement. “The vast majority of these vacancies are directly related to staffing shortages.”

Seely said it isn’t simple to transfer people out of the hospital and into vacant beds.

She pointed to a “broken system,” where department policies and failure to collaborate keep people in the hospital longer than necessary.

The Department of Health needs to ask Social Development to come assess a patient for long-term care, Seely said, but it can only do so once the patient no longer needs acute care.

But after a request, Seely said it can take months for that Social Development assessment to actually happen.

In the meantime, patients typically deteriorate from the state they were in when they first came to the hospital.

“Putting Mrs. Smith in a glorified ambulance bay, so she can wait until this system figures out what she needs, is not the answer,” Seely said.

“We are actually creating a level of care for this person that far surpasses what it would have been if we … had intervened earlier.”

Lyne Chantal Boudreau, the minister responsible for seniors, said in a statement that the province is trying to get seniors out of hospitals as fast as possible.

The Department of Social Development oversees special care home placements, and Boudreau said the department is making use of the option.

“Social Development is working directly with the regional health authorities and ExtraMural/Ambulance New Brunswick to fully utilize capacity in special care homes, helping to ease pressure on hospitals while ensuring seniors are placed safely and appropriately,” the minister said by email.

But with hundreds of vacant beds across the system, Mazerolle is not convinced.

“We can handle these people, and, and they have very meaningful, full lives in a community that they want to be in,” she said.

“Not stuck in the hospital, in a garage, or in a hallway or in a sort of a bathroom. I mean, that’s ridiculous.”

link