Left to dry: unseen risks lurking on reusable medical devices

As the bright lights blur and consciousness fades during the countdown to surgery, most people are unlikely to be pondering the odds of an unsterilized instrument being used1,2. The US FDA3 noted that “Infections can occur through multiple situations including inadequate cleaning, disinfection and sterilization of reusable medical devices”. For example, an estimated risk of infection transmitted by endoscopy is 1 per 1.8 million procedures, and infectious agents such as Helicobacter pylori, Salmonella spp., Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Strongyloides sterocoralis, and hepatitis B and C viruses have been attributed to gastrointestinal endoscopy4. However, due to a number of factors such as inadequate or no surveillance and low occurrence or absence of clinical symptoms, the true risk of infection is difficult to estimate5. Hospital-Acquired Infections (HAIs) are infections that occur 48 h or more after a patient is admitted to a healthcare facility, which were neither present nor incubating at the time of admission1. It was observed that on any given day, about one in 31 patients has at least one HAI6. Moreover, in the ‘2015 HAI Hospital Prevalence survey’, the CDC reported that about 72,000 of the estimated 687,000 (or 10.48%) patients with HAIs died during their acute hospital stay in the US7.

The occurrence of HAIs has a direct medical cost impact on hospital finances and many researchers have performed analysis to understand the economic benefits of investing in an infection prevention and control program8,9. Additionally, the risk of contracting an HAI can be mitigated by effective device processing2. However, the complexity of device features and the importance of implementing appropriate cleaning processes are majorly underappreciated2,10. For example, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) posted 35,039 adverse event reports related to outbreaks, injuries, and reprocessing failures associated with medical devices in 202411. This is corroborated by ‘Sedgwick’s 2025 US State of the Nation Recall Index report’12 that noted the medical device sector recorded an 8.6% increase in recall events, reaching 1,059 in 2024. This report noted that device failures lead recall causes, accounting for 11.1% of medical device recalls, the highest rate in over five years. Moreover, Ofstead and co-workers13 recently noted that “processing breaches in endoscopes are common and often involve profound errors in multiple steps”. In summary, there are notable published reports highlighting that improperly reprocessed medical devices caused HAIs14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25.

Devices used in healthcare facilities must undergo processing before their initial or subsequent use(s), as outlined by the World Health Organization (WHO)26. This cycle should be managed under a quality system to ensure devices are safe and effective for every use27. Devices requiring cleaning, disinfection, and/or sterilization between patient exposures include those used directly during surgery (e.g., forceps, endoscopes), items with minimal patient contact (e.g., blood pressure cuffs), and even non-patient contacting equipment that is just located in the same room (e.g., monitors)27. However, the ability to effectively and safety clean, disinfect and/or sterilize reusable medical devices remains extremely challenging and is often overlooked2,10.

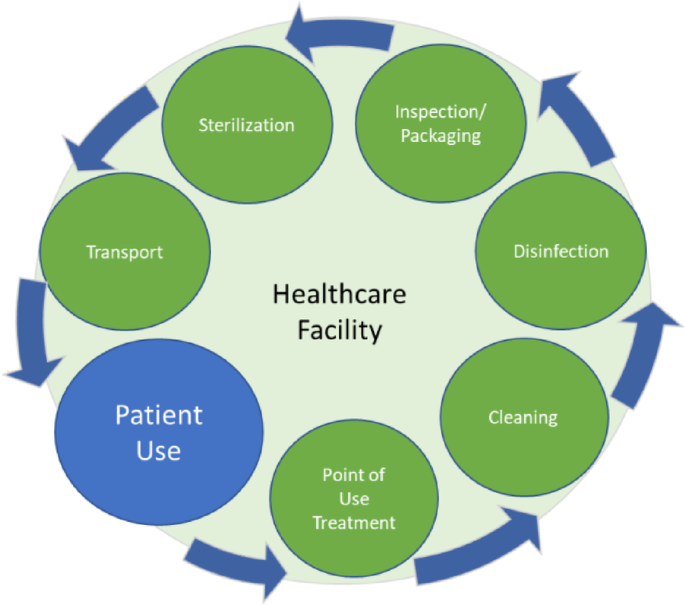

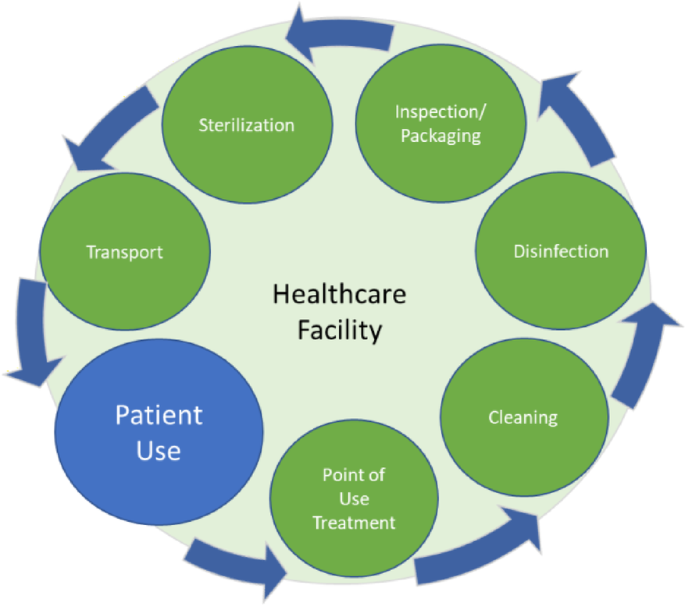

The device processing cycle (Fig. 1) begins with patient use, where the device is in a ready state and is safe for patient use. Immediately following patient use, the preparation for cleaning should begin at the point of use26,28,29. This treatment includes the removal of the visible soil on the device, disassembly (if required), flushing lumens, and brushing hard to reach areas on the device. To facilitate the effective removal of residual soil, instruments should be handled in a way (even if simply covered with a wet cloth) to keep them moist and minimize soil from drying. Immediate treatment at the point of use is a crucial first step in preventing a more challenging cleaning process, potential device damage, or the growth of microorganisms during the waiting period before cleaning30.

Typical processing cycle for critical, reusable medical devices.

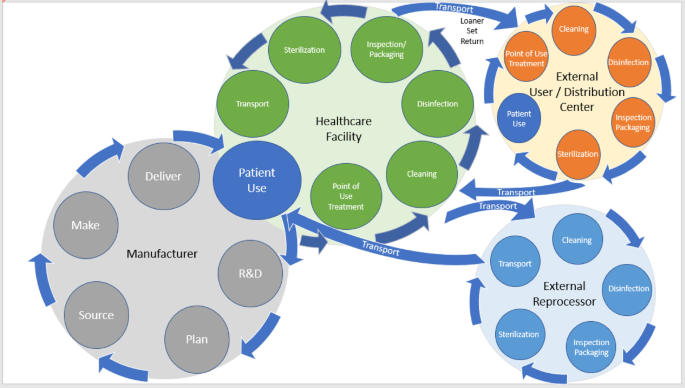

The processing cycle for reusable medical devices is often depicted as a standalone loop (Fig. 1); but the full supply chain is far more complex, involving multiple transfers of responsibility to ensure patient safety (Fig. 2). The process begins with the manufacturer, who is responsible for producing devices with the required microbiological quality, as well as providing IFUs throughout the lifecycle. Once the healthcare facility acquires the device, it assumes responsibility for cleaning, disinfecting, and sterilizing the product after each patient use, ensuring it is ready for reuse1. For certain surgical kits, ownership may be impractical due to cost. To address this, manufacturers or external companies often provide loaner programs. After patient use, these loaner kits should be cleaned, disinfected, inspected and packaged before being returned to a distribution center or transported to another user. While distribution centers may process the kits for reuse, best practices dictate that receiving facilities ultimately process the kits themselves to ensure they are ready and fully traceable30.

End to end device processing cycle.

The complexity of the end-to-end device processing cycle and soil drying is a risk that requires special attention, which can be used to improve the appropriateness of manufacturer’s IFUs1. The guidance provided to healthcare facilities should emphasize minimizing the time between use and decontamination to prevent soil from drying. Recent studies have investigated the effect of soil drying time on reusable medical devices, which yielded results that show prolonged drying can influence subsequent ability to safely process and/or sterilize. An experiment involving a flat stainless steel coupon and a stainless steel hemostatic clamp revealed that prolonged drying of soil increases the difficulty of cleaning, indicating soil solubility decreased as drying time increased28.

Kimble et al.31 explored the chemistry of the protein changes over time and found that the matrix of albumin, which is a primary protein in clinical soils, creates a water insoluble barrier that may present an increased cleaning challenge to remove residual proteins. In order for soil to re-solubilize following drying, water (or the cleaning solution) must integrate into the spaces between the molecules and aggregate to lessen the attractive and cohesive forces holding them together. Then again, as water evaporates from the soil during drying polarity changes, caused by tertiary structural changes, in the proteins can reduce the wetting effectiveness of water, and make rehydration and re-solubilization more difficult. Introducing water into a dried proteinaceous soil initially leads to wetting, followed by swelling of the proteins and aggregates, ultimately ending with dissolution facilitating their removal. However, water alone may not be sufficient to facilitate removal of dried protein and other bodily soils31. Hoover et al.32 investigated the concept of rehydrating dried soil by evaluating whether an extended soak in a cleaning agent could reverse the chemical changes in proteins caused by drying and restore the soil to its original wet chemical composition. Among the cleaning agents tested, only an alkaline enzymatic detergent achieved successful solubility results on the flat surface but demonstrated a decrease in solubility with the added complexity of a device feature (i.e., box hinge). These results suggest that the design features of the device could significantly impact the drying and subsequent removal of soil, making it likely that a standardized drying time for use in healthcare facilities may not be feasible.

In this study, the focus was placed on how the complexity of device design influences the cleaning procedures required for reusable medical devices. The aim was to identify specific device features that necessitate manual cleaning efforts, which become increasingly challenging when soil drying occurs on the device. In the experiment, all aspects of cleaning performance were assessed under conditions that prevented soil from drying. This setup facilitated a comparison between traditional manual cleaning methods—such as brushing and flushing—and innovative non-manual techniques, including soaking, sonication, and automated washing. This investigation highlights the significant impact that intricate design features have on the efficacy and feasibility of cleaning processes, particularly in the face of soil drying.

link